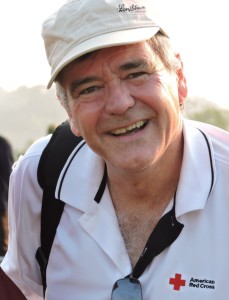

This post was written by Jonathan Aiken, who manages the American Red Cross’s video team.

On Christmas night 2004 I was working at CNN International in Atlanta, anchoring newscasts that few, if anyone in America were watching. It’s not really a big night for TV viewing and CNN International wasn’t widely available in the U.S. For most of those watching, it was already December 26th.

On Christmas night 2004 I was working at CNN International in Atlanta, anchoring newscasts that few, if anyone in America were watching. It’s not really a big night for TV viewing and CNN International wasn’t widely available in the U.S. For most of those watching, it was already December 26th.

Across Asia, people were working; the cities were crowded, and along the coasts, the fishing fleets were out. At beach resorts in Thailand, many tourists were enjoying their holidays. Back in Atlanta, the first wire bulletins crossed around 8:00 Christmas night. A large earthquake had struck, centered off Indonesia’s western coast. No word yet of damage.

A short time later, an AP wire dispatch: datelined Phuket, Thailand (about 300 miles northeast of where the quake originated). Short and to the point, it quoted a resort hotel manager: people were swept off the beach by large waves, and disappeared.

Within 24 hours, we had all seen the amateur video showing water crashing through palm trees in Phuket, and inundating the streets of Banda Aceh in Indonesia. The news would last for days. Some counts put the death toll at 250,000 or more. Scientists say the planet actually wobbled in its orbit.

In the days that followed, people opened their hearts and donated to the American Red Cross. With that generosity, we created the Tsunami Recovery Program, an effort that took the long view towards relief and recovery.

Fast forward to June 2014:

I’m standing on a beach, looking at a beautiful sunset over a placid Indian Ocean near a town in Indonesia most people have never heard of. Calang, in Aceh province, was virtually wiped out by the 2004 quake and tsunami.

But on this clear, warm evening, fishermen tossed nets into the tidal pools and children caught the last few minutes of daylight. The call to prayer echoed from the minarets of nearby mosques.

I had been in Indonesia four days. My assignment: shoot video of the places impacted by the tsunami and capture stories of people whose lives donors helped rebuild. Earlier that day, our group walked through one of Aceh’s central markets — rebuilt by the American Red Cross as part of an effort to restore the local economy. A chicken vendor told me business is good these days. The stalls are bigger, easier to clean, better to work from.

He says “Thank you.”

Riding along the coastal road, moving up into the hills, the views were breathtaking: vistas of blue ocean and lush green hills at each turn. But people who live by the sea know this scenery has many faces. Beauty is only one.

A decade ago, at CNN, I had a front row seat to one of nature’s worst tragedies, and had the job of trying to describe and define the incomprehensible, mostly to people who were spectators themselves.

Now, I’m in the same places I talked about a decade ago, and I’m still looking for words to describe my thoughts. So many times on this visit, I came up short. Instead, I looked…and listened to the memories of those who actually lived through a deadly drama in which I served as a distant narrator. Sometimes, 10 years on, their descriptions are spoken in the present tense.

I interviewed a couple, Yusnidar and Adnan, as they sat on the porch of their small home. Children and chickens roamed in their small yard at the top of a hillside.

A neighbor told Yusnidar to run for higher ground 10 years ago. Adnan and a friend ran toward the sea, grabbing armfuls of Pompano fish left on the beach as the tsunami pulled water away from the shore. The phenomenon is a telltale sign the worst is about to come. He was lucky to make it to higher ground. His friend did not.

Today, they look down on the water from their home, and talk about their work as volunteers with the Indonesian Red Cross. They’re proud of their role in helping their community be better prepared for the next time the water would show another face.

I saw the difference donors made in our visits to the big things…like a water treatment plant that provides clean, safe running water to villages that once relied on a mercury-polluted river for their water. And I saw it in the submerged things, like the root balls of mangrove trees that will improve water quality and stem the flow of the next storm surge.

If the big things can overwhelm, it was a series of small evacuation route signs that brought a human perspective.

I saw them everywhere, starting just yards off the beach and well into the lowlands – in the middle of busy business strips and the edges of farmers’ fields. They show one of those international stick figures moving ahead of a curling wave. All the signs point inland, towards the hills…and in some places, they point towards flights of concrete stairs, cut into the steep hillside and through the brush. The way to safety.

Donors helped build those, too.

The Red Cross invested in evacuation stairs, too, so that young and old, mothers weighed down with children, or fathers loaded with bags of clothes or a few days’ food can move faster towards higher ground.

Towards higher ground. Where safety lies. Where the views are. Where the ocean shows its most beautiful face.