This Black History Month, we are honoring Black men and women whose contributions were essential to our history. Meet Mary McLeod Bethune, whose dedication to academics and equality helped expand opportunities at the Red Cross to African Americans.

As the fifteenth of 17 children and the first child born free to former slaves in 1875, Mary McLeod Bethune rose above humble beginnings to become one of the most prominent black educators, civil rights activists, and stateswomen in the first half of the 20th century.

Growing up in rural South Carolina on her parent’s cotton farm, Bethune did not immediately have access to formal education. When a local segregated Presbyterian mission school opened, Mary willingly walked in order to attend. By age 15, Bethune had taken every subject offered at the small mission school. Her enthusiasm for learning led to a sponsorship to attend the Scotia Seminary, a boarding school in North Carolina. After graduating from Scotia Seminary in 1894, Bethune received a scholarship to attend the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. During her continued studies, Mary’s passion for learning led her to dedicate her life to the education and betterment of African Americans.

In 1904, Bethune opened the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls. Over time, the school grew and merged with the all-male Cookman Institute of Jacksonville, and by 1931, became the Bethune-Cookman College.

As a leader of racial and gender equality, Bethune became president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1924 and a founding president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1935. By 1936, she was serving as an advisor to President Roosevelt and she became the highest ranking African American woman in government when the President named her director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, making her the first African-American woman to head a federal agency.

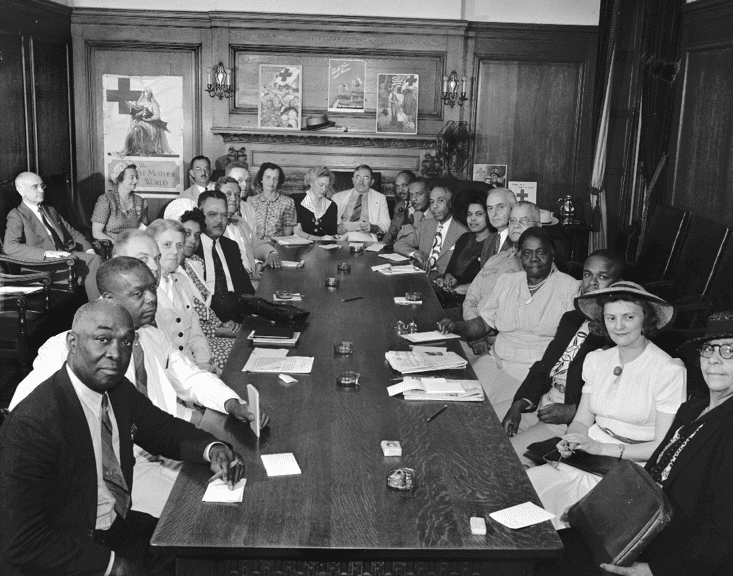

As an advisor to the president, Bethune was invited to two American Red Cross wartime conferences to discuss African American representation within the organization. As a result of these conferences, the “Committee on Red Cross Activities with Respect to the Negro” formed. Bethune was one of five committee members who made recommendations on the blood plasma project, the use of African-American staff in overseas service clubs, the enrollment of African-American nurses and the representation of African Americans on local and national Red Cross committees and staff departments.

Thank you, Mary McLeod Bethune, for your meaningful contributions to the Red Cross, the U.S. government and education in the African-American community.