Along with many other New York City residents, Marjorie Bonynge went to Pier 88 on West 49 Street to see the wreckage of the French liner SS Normandie which had caught fire and capsized while being converted into a U.S. troop transport.

The burning of the ship in February 1942, just two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the U.S. into World War II, galvanized the city. Like many other concerned citizens, Marjorie decided to help with the war effort.

Marjorie’s father was a surgeon and her mother a nurse, so she came from a background of public service and helping others. The 27-year-old enjoyed life in the city and her association with the Junior League of New York. It was the Junior League’s service requirement that brought Marjorie to the American Red Cross.

In 1941, in coordination with the Red Cross, the New York Junior League began a War Relief Unit. Junior League volunteers worked as Red Cross Gray Ladies, nurse’s aides and hospital escorts. They prepared surgical dressings, knitted sweaters for Allied soldiers and sailors,and enrolled in first aid classes.

While Marjorie found these activities admirable, she wanted something more action-oriented. She loved to drive, so she joined the Red Cross Motor Corps. And because she was familiar with medical procedures, she drove one of the first blood donor service-mobiles.

The Motor Corps was staffed almost entirely by women, who clocked more than 61 million miles nationwide while answering 9 million calls to transport the sick and wounded, deliver supplies and take volunteers and nurses to and from their posts. In all, 45,000 women served in the Motor Corps during World War II. Most drove their own cars and many completed training in auto mechanics so they could make their own repairs.

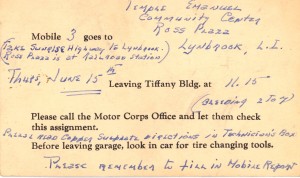

Shown below is one of Marjorie’s assignment cards, sending her to Lynbrook, Long Island, for “bleeding from 2 to 7.” Besides driving, Marjorie’s duties included doing hemoglobin tests once at the donor site. She also oversaw the nurses who were taking temperatures and checking pulses.

Volunteers were required to wear a Red Cross uniform. While Marjorie (shown at right) wore her uniform with pride, she did complain, “Hot, those uniforms were. . .we had to wear those lightweight wools year-round, with a shirt inside and a wide black belt.” Cotton uniforms were available, but for indoor use only, not for drivers. Since Marjorie was both driving and working indoors, she was stuck wearing the woolen uniform.

Her daughter, Susan Strange, says of her mother’s service, “My mother often spoke fondly of her days navigating New York’s streets as she did her share to help the ‘boys’ fighting overseas. She loved to drive, and she wanted to contribute to the war effort, so volunteering with the Red Cross Motor Corps was a perfect fit.”

Loved this post? Check out #WomensHistoryMonth on Twitter. You can also follow post author Nicholas Lemesh, at @NickLemesh.